The Euro: An Unsound Idea

The history, development and structural flaws in a common European currency

The Euro is a rather controversial topic. Again I’d like to remind you that the view here is purely structural, and not a trade solicitation. Will the Euro collapse in the next two years? Probably not. Will it collapse in 200 years? Possibly.

The History of the Euro

The Euro is a common currency across several countries in the European Union (the EU). This ‘zone’ of countries with the Euro as their official currency is called the eurozone.

How old is the concept or idea of a common European currency? Maybe it originated in the 1960s. 1950s? 1940s?

It actually originated in the 1920s, when in 1929, the foreign minister (and former chancellor) of Weimar Germany - Gustav Stresemann wanted a common currency. Remember that Weimar Germany had just been through a period of hyperinflation, and therefore wanted economic stability.

Stresemann went to the League of Nations to ask for a common currency (and didn’t get it). There was already a monetary union, that had disintegrated post-WW1, called the “Latin Monetary Union”, consisting of France, Italy, Belgium and Switzerland,

This disintegration, was fresh in the minds of policymakers. After 1929, the Great Depression destroyed economies all over the world, and the last thing policymakers were bothered about was a common European currency.

Fast forward to 1971. Bretton Woods collapses. Currency start to float, free from their gold pegs, and the higher levels of inflation and devaluation that followed led to the establishment of the European Monetary System (EMS). (Yep, it’s that thing which George Soros shorted and made a ton of money).

The EMS entailed a “European Currency Unit” (ECU), purely used as an accounting measure. Since currencies were fixed or forced into tiny bands. This was to control moves in exchange rates, and counter inflation. You can read more on how pegs work, and why they fail in my thread:

In 1988, the European Council started to talk and negotiate on monetary co-operation. Remember that multiple countries using the same currency would require a single monetary policy imposed on different countries. Other than the UK, the ‘major’ countries in Europe supported the creation of a common currency. Margaret Thatcher, the British PM, was anti-Euro, and the UK didn’t join. In fact, France in a way ‘blackmailed’ Germany into supporting the Euro project — the French and the British were against the re-unification of Germany post the collapse of the Berlin Wall.

The French said they would support the re-unification IF the Germans supported a monetary union. The Germans said yes.

In February 1992, the famous Maastricht Treaty was signed, which officially set in stone the creation of the Euro. The UK didn’t sign it, and to this day continue to use the Pound. As we’re aware, the UK exited from the EU after the “Brexit” vote.

Maastricht Treaty is a landmark example of international co-operation on something as sensitive as currency. Denmark wanted to opt-out, just like the UK. Denmark however, unlike the UK, pegged its currency to the Euro, at 7.46 DKK to 1 Euro, and has a 2.25% band either way.

The Euro officially came into circulation on January 1, 1999. How did the other countries “converge” into the Euro? They became either fixed, or trading volumes dropped. Dealers were shocked at how quickly Deutsche Marks became untraded.

The Euro’s first day of circulation was at $1.1686 to 1 EUR.

Acceptance Into the Eurozone

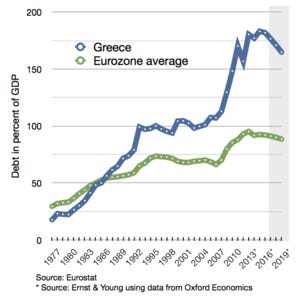

The Eurozone countries had a lot of strict conditions to meet. One is the famous restriction of having a budget deficit of <3%, and having Debt/GDP being <60%.

Greece couldn’t meet these conditions and wasn’t a “founding” member of the Eurozone and was still using the Drachma till 2002, when it joined the Eurozone. Greece really found it difficult to stay under these conditions. After all, when they can borrow at really low rates, why not spend? The Greek government is very good at one thing - spending money they don’t have, which is an issue when you have a 3% deficit limit.

(Source: Vox)

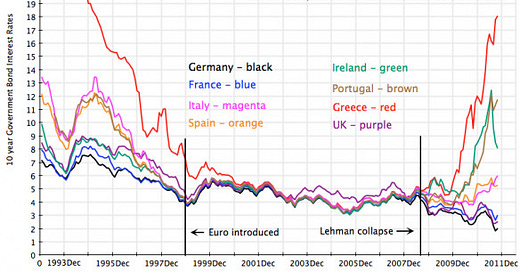

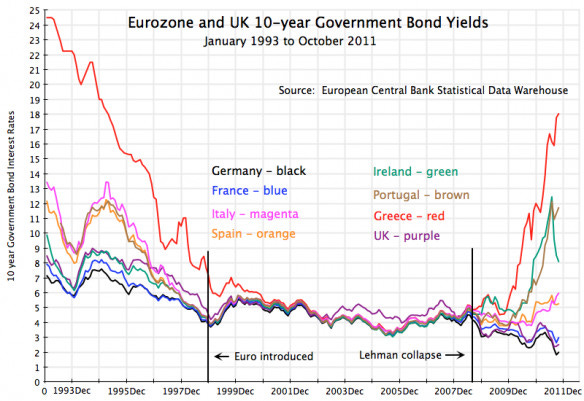

In the early 1990s, Greece saw their bond yields above 20%. During the mid 2000s, they got to borrow at low single digits, so it was very attractive for them to spend. The unfortunate thing here is the Greeks forgot that they no longer control their monetary policy - they’ve traded control over their monetary policy in favor of a fixed exchange rate and (temporary) stability.

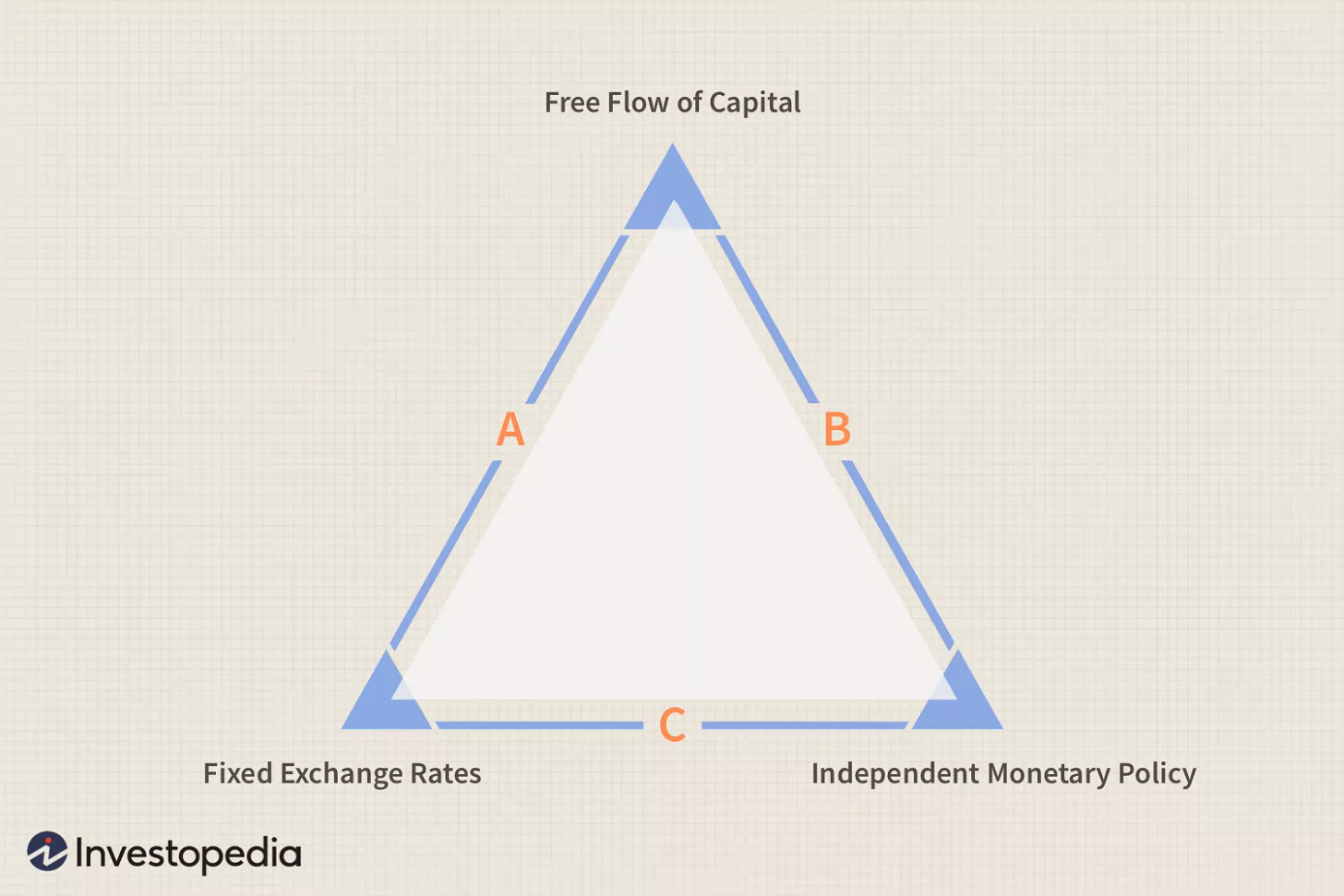

The Impossible Trinity

There is a famous trinity in the study of currency economics - also called the ‘Trilemma’ or the ‘Mundell-Fleming Trilemma’.

(Source: Investopedia)

This trilemma is extremely important when analyzing the Euro, because you can only pick two out of the following three:

Fixed Exchange Rate

Independent Monetary Policy

Free flow of capital

The average non-eurozone country has picked an independent monetary policy and free flow of capital. For example, Canada has relative free movement of capital into and out of the country. Canada also has independent monetary policy - the BoC is free to make decisions on interest rates and the ‘quantity’ of money, based on what they believe will benefit Canadians economically. Similarly with New Zealand, Britain, Australia, etc.

The Eurozone members have chosen a fixed exchange rate regime and a relative free flow of capital, and given up independent monetary policy. This is very significant, because you have to ‘make-do’ with whatever monetary policy is forced on you. This is the worst, because if you’re an unimportant country, it becomes very difficult to get the ECB to pay attention to you and your specific needs - why worry about Andorra when you have Germany to worry about?

This leads important countries to dominate the Euro, while smaller countries are just pushed to the periphery. PIGS, Germany and France are the major countries dominating this arrangement. PIGS stands for Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain (though occasionally it’s PIIGS, including Ireland).

The Euro functions in effect as a 1-to-1 peg. 1 ‘German’ Euro is nominally worth 1 ‘Italian’ Euro, because it’s the same currency. Pegs have historically never worked, and likely will never work.

This trilemma is why the Euro is an erroneous arrangement.

The Politics of the Euro

It is important to keep in mind that the Euro was a political objective, through a monetary project.

Historically, Europe has been plagued by wars and conflicts, relating to the national interests of the various major powers in Europe. To that end, it is a mechanism for stopping the war. In a sense, it works - if you have to fight a war, you typically inflate and print your currency. But since you’re not in control (ECB is a pan-Eurozone bank) you can’t do that. Similarly, your currency depreciates in times of war. The Euro is a means to an end to do that.

But the economic costs of such an objective are enormously high.

Directly from this point one will realize that as long as European politicians have the will to keep the Euro intact, it will stay intact. However, once politicians give up on the Euro project, the Euro will then start to fail.

However, at the moment the will is strong. The famous “whatever it takes” from Mario Draghi is not just an economic commitment, but it is also a political one.

The Euro Crisis

The Euro really came into question during the Eurozone crisis / European sovereign debt crisis that followed the Great Financial Crisis. This is where the ‘PIGS’ countries had their debt come into question.

In 2015, Greece famously (or rather, infamously) defaulted on its debt.

Greece, as previously mentioned, suffered from high inflation and instability because of expansionary fiscal policies that the Greek government carried out. The hope was the Euro would allow Greece more stability, lower rates, increased flow of capital, increased investment and help spur economic growth. Tax evasion in Greece was rampant, where wealthier people under-reported income and over-reported debt payments, leading to lower revenue via taxes for the government and increases in deficits.

Two things Greece had not thought of was the downsides of:

Being a non-dominant country in the eurozone

What happens to other parts of its economy

Greek goods and services were expensive relative to Germany, and this negatively impacted its current account (importing more than it exported). Greece gave up independent monetary policy, as we previously discussed, and this meant they can’t devalue their currency.

Germany however enjoyed a lot of growth by the Greeks using the Euro. They produced cheaply in Germany, and sold in Greece. Banks lent to Greece, which had to borrow to afford these goods and services. But as long as things were okay, nobody asked questions.

The Great Financial Crisis started asking questions of the Greek economy. The right solution to a crisis is to increase the amount of government spending, which helps boost aggregate demand, and keep the economy more stable. But, remember the 3% maximum budget deficit?

The Greeks had to follow this, leading to austerity, 12 rounds of tax increases, riots, and 25.4% unemployment. This too, was accompanied by lower tax revenues (it was a recession after all).

The IMF had to step in with a bailout package, to help Greece. However that did not suffice. Prior budget deficit numbers were discovered to have been underreported.

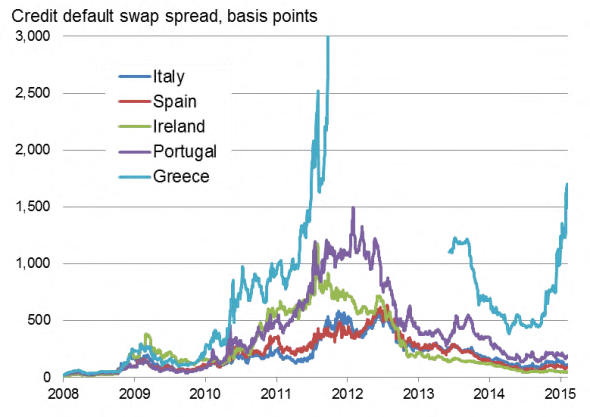

The Greek debt numbers were much higher than the general eurozone, and this led to an increased risk of default, which eventually happened in the year 2015. The spread on credit default swaps (insurance on Greek debt) went through the roof:

(Source: IHS Markit)

This is where the loss of control over monetary policy became an issue. A country that can print its own currency can never default - they can just print (at the cost of inflation, of course). But a country that cannot has to allow another central bank to dictate its outcome.

So here is the question - who does the central bank try and help? Just Germany and France? Or does it help the ‘poorer’ countries like Greece? In a sense Greece is torn between a fire and a frying pan - does it allow the ECB to dictate austerity? Or would it rather have larger deficits, likely lower investment and lesser economic stability?

Summing Up the Case Against the Euro

I would like to remind readers that this post is not written expecting an imminent collapse in the Euro. It is to purely highlight the structural flaws that come with not having control of your monetary policy.

But here is the case summed up:

Lack of control of monetary policy, which leads to major economic issues, as seen in Greece

The existence of a monetary union, and a central bank, but no fiscal union. We have the ECB, but the fiscal union does not exist - France spends what it likes, and the Netherlands spends what it likes.

The lack of other institutions that can help countries where the monetary policy doesn’t “fit” correctly, which the Maastricht treaty failed to create

It is a monetary solution to a political problem. The main problem in Europe was political instability, risks of war, etc. This was solved by everyone joining a common currency. In a way this works - when you go to war, your currency gets inflated (governments print money to pay for wars), and this is far less likely. But there’s far better solutions to this.

A lot of countries are in it for the temporary bouts of economic stability, and lower interest rates, which creates the wrong incentives for those countries

The solutions to these issues deserve a post by itself, and would make this (already very long) piece even longer. But this is something I’ve been reading quite a bit about, and hope you liked it! Do share if you did!

Good article. The “Trilemma” is the basis for much anti-eu sentiment. The free flow of capital is one of the basic EU freedoms (free flow of capital, goods and people), with the euro, you basically give up the exchange rate. Now, all of a sudden, you have lost sovereignty over monetary policy. This was never pointed out by the politicians when the Euro was introduced. People don’t like the loss of sovereignty, therein lies the root of anti-EU feelings.

Good article. I agree with your view.

"The existence of a monetary union, and a central bank, but no fiscal union"

The big issue in EU is a monetary union without a political union. Why would Germans subsidize the citizens of another country like Greece? Transfer payments is one way to solve for economic differences and this isn't possible without a political union and a national spirit.

The USA is a counter-example in this regard. The different states live together in a political, monetary, fiscal union and there is a common sense of national belonging.

No one asks the question as to why California is subsidizing Alabama.